Definition & Example

A blockchain is a type of distributed ledger network that records transactions in a string (chain) of groups (blocks) of transactions. A blockchain is cryptographically secure, decentralised, append-only and updated by a consensus mechanism.

Decentralised has been explained in the Distributed Ledger note. Append-only means that blocks of transactions can only be added to the already accumulated and agreed blocks. Previous transactions cannot be amended or canceled; a concept also referred to as immutability. A consensus mechanism is a method of agreeing across nodes of the ledger which transactions are valid and should be included within a block of transactions (hereafter simply ‘block’). The term cryptographically secure simply means that mathematical methods are used to encode and authenticate the data to ensure that data cannot be tampered with.

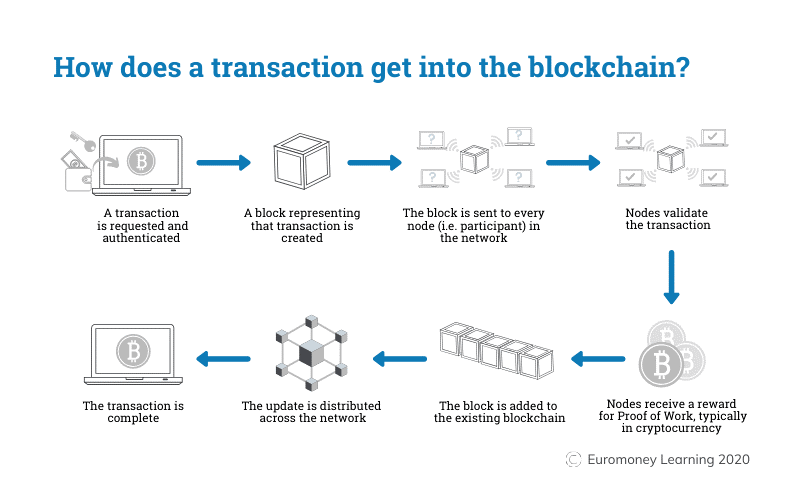

In a blockchain, a ‘new’ transaction or block that has been requested is validated by all the participating nodes in the network; all the nodes effectively check if the debited party has enough in their account, or wallet, to make the transaction and that there is no double spending occurring. When the majority of nodes agree, the transaction is added to the chain and distributed across the network. Each block in the chain is mathematically tied to its predecessor thus any attempt by a node to replace or change a prior block can be detected by the rest of the network. See 'In Pictures' below for a diagram showing this simply. Remember that the account of record could hold anything that can be counted: cash, assets, votes, social media likes.

Imagine playing a game of Monopoly with strangers in which you have the board, pieces, and properties, but no paper money. There are however paper and pens, so you all agree to use the paper to record each transaction made between the players to track cash balances of all the players. Everyone will record the same transactions, and track the balances of all players, to be sure that there is no cheating amongst the group.

As each purchase is made, and each rental transaction is paid, the players around the table ensure the starting balance of the player making the payment has enough credit to make the payment. If the players agree this is the case, then they record the transaction. Should one of the players miss a transaction or mis-record a transaction, then any dispute is resolved by a majority vote. Note that this means the players must announce each transaction to all of the others for agreement and to have it recorded.

Monopoly is notoriously lengthy in game-time. Researching disputes through an ever-growing list of multi-party transactions is both tedious, time-consuming, and difficult to maintain. The players thus agree when they reach the end of a page (which they should all do at the same time if they’re recording the same information) they will each sign all of the pages and use the closing balance of that page as the starting balance for the next page. This means that transactions can be tracked on a page-by-page basis. The signed pages are stapled on to the top of each player’s stack of pages and put aside.

Should there be an attempt at any point for a player to manipulate their current balance, by say attributing their own account to have more money than they really have, then only page starting and end balances can be compared for transactions prior to the current page. If that player has also substituted a false page to back up their false balance, the other players can quickly check whether that false page has all players’ signatures on it, which will of course not be the case, since each page is fully signed at point of agreement.

In this, admittedly drawn-out analogy, the players are nodes in the network, each page is a block, the signatures act as the cryptography, and stapling the next page to the top represents the append-only nature of the chain, which is the full batch of completed pages.