Definition & Example

A smart contract is simply a piece of code, or a program, that automatically executes pre-defined actions upon certain conditions being met. Essentially, smart contracts represent automated versions of real-world contractual obligations. Although the term has taken off since the advent of the Ethereum blockchain in 2015, and is usually used synonymously with decentralised applications residing on blockchains, in fact, smart contracts have been with us in electronic form since the start of e-commerce on the web, and indeed the vending machine [1] has been noted as the earliest form of technology to incorporate a smart contract. A blockchain is not necessary to have a smart contract.

To understand this further, consider the fact that virtually all contractual agreements in society involve the exchange of two or more things between at least two parties. Those things could be commodities, intellectual property, permission to use a piece of personal data, your time (i.e. wages), cash, securities, etc. In dealing with others, a legal contract serves as a form of written insurance that you had an agreement, in order to deter dishonest actors from being tempted to renege on the deal, for instance by selling something they don’t own. A further way of managing the inherent trust issue, for example with large financial deals, is to use a third-party intermediary to hold the two items being exchanged in escrow, with the party releasing the items to the new owners upon receipt of both. All for a fee, and likely taking place over a significant time period; buying a house still operates largely like this today.

Imagine instead that a computer program can verify that both parties have the items, then potentially the need for a third party is eradicated, or at least some form of security is automatically extended to both transacting parties. As with most automated processes, this should remove a lot of inefficiency in the process.

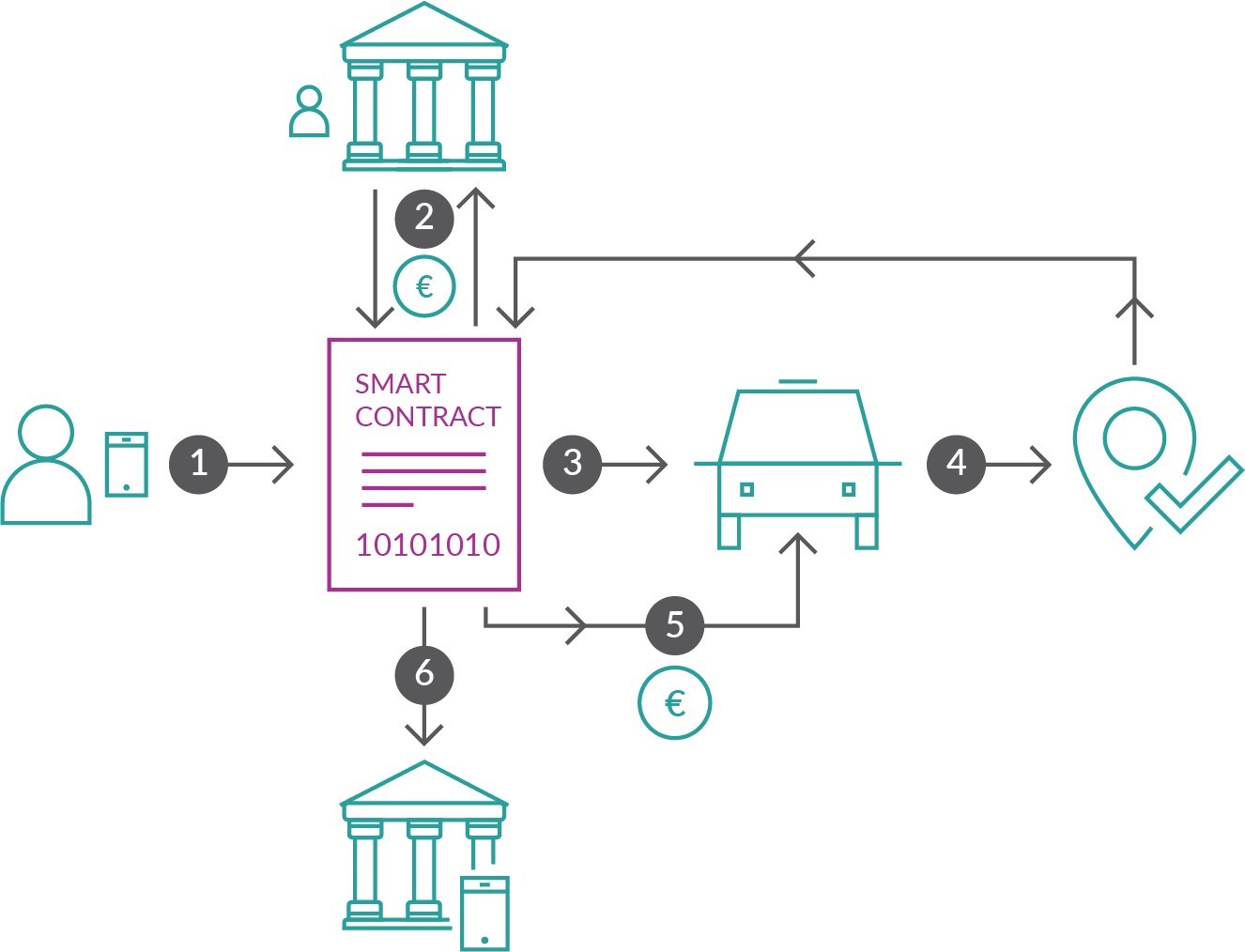

An example (see 'In Pictures' below) of a smart contract that many of us in large cities interact with regularly, is through the Uber app (or a similar taxi-hailing application)[2]. When booking a ride, the app uses your payment method to determine that you have the funds to travel, that the 'from' address exists and is reachable (similarly with the 'to' address), and then when satisfied, arranges for a driver.

In actual fact, as can be seen with a retail banking app on your device, at the point of requesting a ride Uber debits your account (cue notification of spend from the bank) and holds it until completion of the ride. If a driver is not assigned or they cancel, then a similar notification indicates your funds are refunded to your account. If, however, you ride and the driver completes the trip, then the condition that the driver has provided his time and service is met, and at that point, Uber releases the funds (minus a fee) to the driver. In this example, a smart contract has ensured the exchange of two ‘items’ (your cash and the driver’s time and fuel) in a way in which both you and the driver feel confident that neither is at risk of losing out. In a similar way, smart contracts in capital markets can automatically execute a range of actions, be it trading in securities, ensuring delivery vs payment, or validating that collateral provided meets the agreed schedule. More on this in the next section.

For a more technical dive into smart contracts, there are materials listed under 'Further Reading'.

-

[1] Savelyev, Alexander (14 December 2016). Contract Law 2.0: “Smart” Contracts As the Beginning of the End of Classic Contract Law. Social Science Research Network. SSRN 288524.

-

[2] The subsequent description of the workings of the application have been deduced by author from observation of the app and financial movements, and this should not be taken as a technically complete or accurate description of how Uber processes its rides.